Publicité

Analysing judgement of Emtel vs ICTA and others case: Why the defendants should appeal and some potential grounds to do so

Par

Partager cet article

Analysing judgement of Emtel vs ICTA and others case: Why the defendants should appeal and some potential grounds to do so

My reaction to learning the outcome of judgement 2017 SCJ 294 must have been similar to many other fellow countrymen. Again taxpayer’s money would have to go and fill the coffers of private interests! This has become a seriously worrying trend in the country and while in some cases this may be justified, we should all be concerned about the root causes leading to these situations.

Out of professional curiosity, I then dived into reading this heavy judgement (89 pages and 361 paragraphs) and my initial reaction, confirmed by going through and analysing the whole document was: 1.) What a weak defense and 2.) for anyone with a sound (humbly said!) knowledge of the telco industry, the plaintiff’s case, if well countered, should not have led to the payment of this huge amount!

It is not my intent to impute motives but it would appear that the defendants were strategically baited and played right into the hands of the plaintiff’s lawyers. They seemed to have been unable (why?) to provide an alternative context to the issue at hands. Indeed the learned judge was so kind as to indicate this. In paragraph 356, she writes “After the decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the year 2000, it would at least be expected that the Authority, MT and Cellplus would have taken heed of the observations therein and proceeded at least to a narrowing down of the issues but it did not happen.” In Paragraph 269, she uses the word “uncontroverted” to imply that the defendants did not refute the plaintiff’s core arguments.

This article constitutes a humble attempt to provide some cues as to how the case could have been defended. There are some obvious limitations to this exercise as 1.) I am basing myself on the judgement text only and do not have access to all the relevant filed court documents and 2.) a simple article cannot englobe all the aspects of a very heavy, complex, highly technical and filled with ambiguity (of interpretation) court case 3.) some of the figures I present below are rough estimates and should be refined through more in-depth and time-consuming calculations.

Let’s start by some historical perspective (boring but necessary)

All governments worldwide have considered telecommunications as a strategic enabler for growth and economic development. In the 1980’s, technological progress in electronic systems made the market ripe for liberalisation. In 1982, telco monopoly was abolished in the UK and in 1984 British Telecom was privatized. The real big bang occurred in the US with the dismantling of AT&T in 1984 and pressure was exerted worldwide by the US government for other governments to follow suit and open their local telco markets to competition.

Europe had to follow and in 1988, after having published a series of recommendations (as from 1984) and a green book (in 1987), the European Commission published its first directive (88/C 257/01) to enforce telecommunication liberalisation in Europe. A series of directives followed till 1996 out of which three are of major interest to the matter at hands: i) directive 90/387/CEE published in 1990 and which pertain to interconnexion of telco networks, ii) COM(94)145-final “Livre Vert Sur Les Communications Mobiles Et Personnelles” published in 1994 and iii) directive 96/2/CE published in 1996, titled “…en ce qui concerne les communications mobiles et personnelles”.

Note: These directives shall also be used as reference in chapters below.

The then Mauritian government can therefore only be lauded for having kept pace with international events (in some case being precursor) and for providing a license for mobile operations to the plaintiff in 1988! Considering the level of economic development and the lack of exposure (maybe lack of skills also) at that time, the regulatory environment was bound to be imperfect and there has to be a learning curve to regulate the market efficiently. This was not any different worldwide and it is queer that our government (through the regulatory body) now has to pay for that. There should have been research by the defendants as to whether there are precedents.

Indeed, as a comparison, EC directive 88/C 257/01 provided 4 years for EU governments to implement liberalisation of their telecom markets. EC Green book COM(94)145-final was issued in 1994 and directive 96/2/CE which addressed regulation and liberalisation of mobile telecommunication in 1996 only (which is the start of the plaintiff’s claim period).

This liberalisation was effected in the EU by countless highly trained engineers, legists, public servants and finance professionals at that time. It should not be preposterous to say that tiny Mauritius had no such available resources and imperfections were bound to occur for which, it is my belief, there should be no penalty. Private businesses should be fully aware of the market (and the associated risks) where they intend to operate and they do so “en toute connaissance de cause”.

EC Green book COM(94)145-final also provide some valuable insight on the upcoming trends at that time. In particular, it states :

- « Abolition des droits exclusifs et spéciaux dans ce secteur pour l'exploitation de systèmes de communications mobiles. Il y a droit exclusif lorsqu'un Etat membre réserve un service à une seule entreprise publique ou privée dans une zone géographique donnée. »

- « il s'agit de passer des technologies analogiques aux technologies numériques, et d'un marché spécialisé au marché grand public. »

The description made in points 1 & 2 above fits the plaintiff description of its license and its operations from 1989 to 1995. In short, it is not wide off the mark to state that the plaintiff was operating as a monopoly using a technology (TACS) officially deemed obsolete in 1994.

The above is very important in setting the context and debunking the plaintiff’s arguments. I will further address these in section “Economic Perspective” below.

Note: The reader may ask why I have made so many references to the European telecom context and regulations. This is because the plaintiff has made ample references to international jurisprudence and regulations in its claim and I hence providing counter-arguments of similar nature.

From an Economic Perspective

On the status of monopoly, I believe there are enough textbooks in economic theory to support my claim that an “efficient” monopoly is nothing short of a miracle. At the very least, it should be “un exception qui confirme la regle” that monopolies are usually inefficient. Further, in general, once there is an established monopoly, there is only a short-step to rent-seeking behavior.

“Rent-seeking behavior is most common when the rent seeker is also a monopoly or has sufficient economic or political power to act as one. The concept was originated by Adam Smith.”

This is where judgement 2017 SCJ 294 is very disturbing. An elected government mission is, among others, to sustain free & fair competition and lower prices (without dumping) to the benefit of its population. Judgement 2017 SCJ 294 may have created a dangerous precedent whereby private interests, which were in a situation of monopoly, will feel encouraged to sue government once they face competition through enactment of regulations and thereafter pricing margin squeeze.

Looking back at the judgement, the defendants were not strong enough in establishing the status of monopoly of the plaintiff. They could and should have moved that all the pre-1996 complaints put forward by the plaintiff be dismissed on the ground of being mere “cry-baby” tactics to protect an existing private monopoly with potential rent-seeking behaviour. More on this from a technical perspective below.

Interestingly, nowhere in the judgement document, the plaintiff stated that they had any intention to invest in GSM. As a note, works on GSM specifications started in 1983 and were finalized in 1987. The first GSM call happened in Finland in 1991. EC Green book COM(94)145-final mentions «il s'agit de passer des technologies analogiques aux technologies numériques, et d'un marché spécialisé au marché grand public.»

It is expected that the plaintiff was keeping abreast of worldwide evolutions in the telecommunication industry and therefore had ample time to pre-empt defendant 2 decision to launch GSM technology. The absence of such evidence in their claim would serve to reinforce the doubt of rent-seeking behaviour.

I would repeat myself: The then-government(s) should be lauded and not penalized for having showed strategic vision and thus encouraged and supported the installation of a GSM system in Mauritius in the early 90s. This decision has served to boost economic growth and the attractiveness of the country (with regards to the tourism industry for example).

As a favorable comparison, EC directive 90/388/CEE states: «considérant que le renforcement des télécommunications communautaires constitue l'une des conditions essentielles du développement harmonieux des activités économiques et d'un marché compétitif dans la Communauté tant du point de vue des fournisseurs de services que des utilisateurs;»

This would serve to rebuke paragraph 131 as it should have been made clear by the defendants that the investment in GSM technology was first and foremost in the strategic interest of the country and not to derive commercial rate of returns.

Also, that the plaintiff was not prepared to react to a changing and evolving industry and resorted instead to “cry-baby” tactics to protect their position should be their own misfortune. After all they benefited from 7 years of monopoly. Many would have considered this as winning a mighty lottery. How and why they could not stand strong when competition came should certainly not imputed to other parties.

The discerning reader will recall that similar “cry-baby” tactics were resorted to when a French competitor came asking for a 3rd mobile license in Mauritius.

From a technical perspective

Let me state it right away: GSM is a vastly superior mobile telephony system to any 1G system that were in operation during the late 80’s and 90’s. How? The bells and whistles that come with any new ICT technology do count though these were weakly presented by the defendant 2 & 3 but foremost, there are keys aspects to the engineering of the GSM system that give weight to my statement and these were completely missing in the defendants arguments. Let’s focus on one of them: Spectral Efficiency.

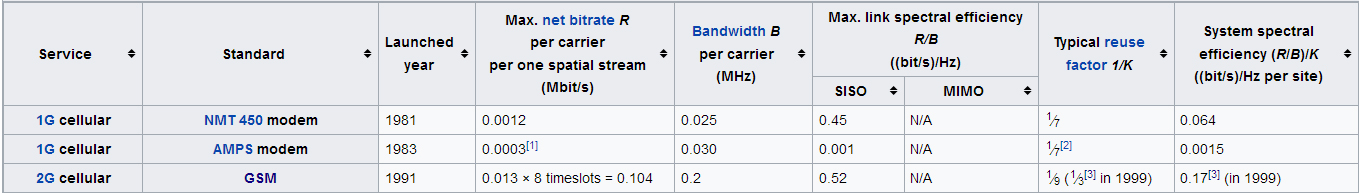

This barbarous term (to the non-specialist) is related to the radio waves which a mobile telephony system uses to carry our voice calls (and other types of traffic such as data) between the caller and the recipient. Radio waves are defined by their frequencies and the amount of information that can be fitted into a frequency carrier for a unit of time is called spectral efficiency. Below the comparison:

Note 1: TACS is a variant of AMPS.

Note 2: These are theoretical figures and live operational figures will be lower.

Note 3: It is assumed that the coverage area for different technologies are the same.

As illustrated in the above diagram, in 1996, GSM systems had a spectral efficiency of 0.06 (0.52/9) whereas AMPS/TACS was rated at 0.0015. GSM could be up to 38 times more efficient than AMPS/TACS !!

As an analogy, defendant 3 had a bus, which could potentially carry 38 times more passengers than the plaintiff’s bus (which was also older). Notwithstanding operational cost differences between both parties, it is safe to assume defendant 3 had an intrinsic large competitive advantage on technical cost per unit transported, which he used to his benefit.

In addition, GSM systems were engineered to be highly scalable and hence to cater for mass communications.

Thus in a competitive market, it would be reasonable to assume that the party benefitting from a large competitive advantage providing a higher profit margin potential, would leverage on same in order to maximize its available sellable capacity, capture volume by lowering prices and still make a heavy profit over time.

- Let’s now have some words on the pre-1996 period whereby the plaintiff claimed that defendant 3 has installed and was testing its network without licensing.

Firstly it is common courtesy to obtain such an authorization to do pre-licensing tests when a telecom operator is dealing with innovative technologies requiring massive capital expenditures and for which operational knowledge is still thin. This is a risk mitigation action in order to obtain better comfort that the technology actually works in its targeted operating environment and to assist in finalising contracts with the technology vendors. There is a high probability that the plaintiff has benefited from similar courtesies during the course of its operations.

Secondly, the installation, configuration and commissioning (testing) of a GSM system is a hugely complex and time-consuming exercise. This is was even more so in the 90s where the technology was still immature, skilled-resources were scarce and operational knowledge/experience were still lacking. From my personal experience, a turn-key GSM network installation could take anything from 6 months to 2 years depending on the country size. A prudent operator would certainly ensure that, in its launch strategy, this testing period is accounted for.

In terms of commissioning, the unique radio engineering features of GSM required the network to be load-tested in order to ensure that service-level agreements (telcos talk about QoS – Quality of Service) and contractual key performance indicators between the GSM vendor and operator were met. The longer the testing the better it was in order to detect and address issues.

In addition, GSM networks came with complex IT-based billing systems which were also required to be tested in depth to ensure accuracy and completeness of customer invoicing with regards to different call traffic scenarios. For this, live customers were required to be on the network and generate traffic by using the available services (including international calls on which the defendant 3 made a judgement call to bill customers in order to avoid abuse).

Defendant 3 was therefore absolutely justified to onboard friendly users to test its network. From my professional perspective, 4000 users is a reasonable figure to stress-test the network over the size of the island and in my view this should never have been construed as operating without licensing by the learned judge (again some weak defense by the defendants).

Defendant 3 should have moved to repeal these pre-1996 and pre-licensing claims (paragraphs 67, 68, 70, 71, 72 & 346) by the plaintiff as being nothing but frivolous.

- Let’s have some final words on paragraph 42, the plaintiff claims that it was prevented from expanding by not being allocated additional frequencies. While I do not have all elements at hand to present a defense against this claim, it’s worth noting the following points:

- The trend according to the European Commission in Green book COM(94)145-final was, as follows: «Le Conseil estime aussi qu'il importe de promouvoir l'utilisation la plus efficace possible du spectre des fréquences en tenant compte, en temps utile, des besoins exprimés par les prestataires de services et des utilisateurs compte tenu du développement industriel et de l'élaboration des normes.»

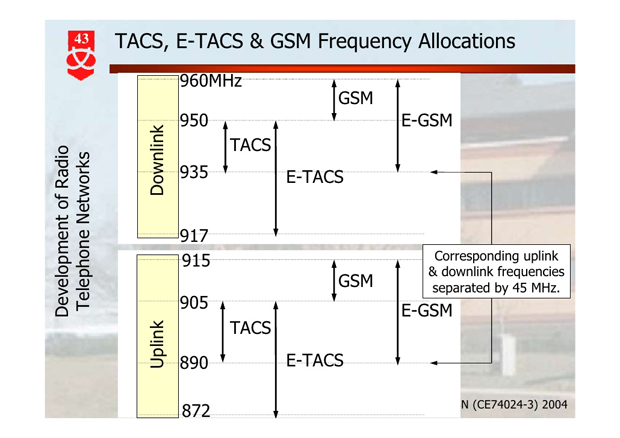

- It is already proven above that TACS system had poor spectral efficiency. Further GSM was expected to operate in the frequency band of TACS at some point of time as illustrated below.

- Frequencies used for mobile communications are a very scarce resource.

- It is common practice for mobile operators to book as much frequencies as possible in order to create virtual entry barriers for new players and it is the responsibility of the telecommunication regulatory authority to obtain proper evidence and determine whether an application for new frequencies is justified.

In the light of the above, it is therefore not far-fetched to assume that in the early 90s, the regulatory body (defendant 1) adopted a prudential approach to the allocation of frequencies.

Labour efficiency perspective

In paragraph, the plaintiff’s expert witness states “As regards Emtel’s labour efficiency, Mr Forrest found that Cellplus spent on average Rs 8, 942 to serve each subscriber with a similar scale operation whereas Emtel’s gross operating expenditure was between Rs 3,576 and Rs 4,494. Mr Forrest spoke to Emtel’s management when he came to Mauritius in 2002 and 2014 and reviewed the actual expenditure of Emtel and the commercial rationale of its expenditure. Mr Forrest concludes that Emtel was efficient at about the time Cellplus launched its service.”

This made me chuckle as I am not a believer in such miracles of labour efficiency. How and why the defendant 2 & 3 did not demolish this highly controverted claim is also beyond understanding. While it is reasonable to expect a difference between a state-owned company and a private one, an above 100% difference between businesses of similar nature and scale is certainly not normal.

A careful analysis would have led to one (or a mix) of the following potential causes for explaining such a difference:

- The plaintiff was largely understaffed to cater for such a business/operations. Two main areas of interest would be technical operations and salesforce.

- The plaintiff was employing low-skilled and unqualified labor to execute its management and operations though it was dealing with a highly complex and technical business environment.

- The plaintiff was massively underpaying its staff which in turn would have led to a lack of qualified & skilled personnel in the company.

- The plaintiff was resorting to cheap international labour (India maybe?)

- The plaintiff was benefitting from cross-subsidy from its parent companies either in the form of outsourced operations or in the form of skilled resources being made available free of charge (Oh-ho!)

The defendants could easily have requested and obtained data to confirm these causes and this would have given them a major counter-argument as to why they were successful in entering the market and the reasons as to why the plaintiff floundered. In my view, if any one of the above causes is averred, the plaintiff should be the one to blame for its woes, certainly not the defendants.

From a market perspective

It is not true to affirm that a lower price is the sole factor for mass acquisition of subscribers in the mobile telephony and therefore the main cause for the plaintiff woes. Lower prices are indeed a contributing factor but it certainly do not account by itself for the mass success, which GSM encountered in Mauritius and worldwide.

To illustrate this, we need to look at what happened when MTML entered the market as 3rd GSM operator with much lower prices than the two existing operators (Plaintiff and Defendant 3). MTML did not create as much as a dent on the market share of its competitors.

In order to understand the GSM phenomenon, we need to go back to strategy textbooks and refer to the most common used example to explain strategy to students: The Ford T-Model! Extract from Wikipedia:

“The Ford Model T was named the most influential car of the 20th century in the 1999 Car of the Century competition … Ford's Model T was successful not only because it provided inexpensive transportation on a massive scale, but also because the car signified innovation for the rising middle class and became a powerful symbol of America's age of modernization. With 16.5 million sold it stands eighth on the top ten list of most sold cars of all time as of 2012.

Although automobiles had already existed for decades, they were still mostly scarce and expensive at the Model T's introduction in 1908. Positioned as reliable, easily maintained, mass-market transportation, it was a runaway success.”

The above description could not provide a better explanation to explain the success of GSM. GSM was cheaper, more reliable, easier to maintain, suited for mass communication and a big symbol of innovation! Its success was therefore a mix of all the cited factors against which the plaintiff had no answer.

To further support this, let look at these extracts from EC Green book COM(94)145-final

«Les études réalisées indiquent que l'évolution vers une utilisation grand public des communications mobiles et l'évolution vers des services de communications personnelles de masse s'accélérera substantiellement…»

«Un an seulement après son lancement effectif, le GSM représente déjà plus de 10% du parc installé de téléphonie cellulaire dans l'Union.»

To conclude this point, the plaintiff suffered not because of anti-competitive behaviour by the defendants or because of a weak regulatory environment but because:

- It was crippled with an obsolete product which had lost its appeal to customers.

- As explained in chapter on labour, it was potentially crippled by an under-par workforce.

- Its commercial strategy which was to address high-end customers was not suited to the technological revolution which GSM brought.

In short, the plaintiff may have been efficient at the period under claim but it was certainly not competitive hence its woes.

Actually the plaintiff indicate themselves that they were not competitive in paragraph 173 stating “The second perspective from which Mr Forrest tests the reasonableness of Emtel’s tariffs is Emtel’s profitability in the same period. Emtel’s accounts show that over the period 1991 to 1995, the profit margin ranged from 2.77% in 1993 to 19.71% in 1992 and 15.88% in 1995. International comparators show that the profit margin was 27% at about the same time and MT realised a profit margin of about 30% over the same period. Mr Forrest therefore concludes that Emtel’s tariffs were reasonable.”

I beg to differ that the lower profit margin was due to reasonable tariffs. The defendants should have dug further to demonstrate the plaintiff 1.) did not do enough to develop the market from the time they started their operations 2.) they were unprepared and unequipped to face competition and 3.) their commercial strategy was out of touch.

From a Finance and Accounting Perspective

This chapter is the crux of the matter as it constitutes the basis on which the quantum for penalty was determined. The previous chapters have shed light on mitigation factors (such as market forces, industry practices and worldwide trends) which, though they affected the plaintiff, were not the result of tortious actions on behalf of the defendants during the period where the claim is set.

A lot could be said on the matter of finance & accounting but I will try cut short an already lengthy article through a few bullet points.

Paragraph 132 reads “The forecast also shows that Cellplus would be making losses during the first six years and would be making cumulative losses for eight years. In the opinion of Mr Forrest, a commercial investor would find this period of loss making long and risky … Mr Forrest plugged in the interconnection charges and calculated the rate of return for the ten year period and according to his calculations, the rate of return in the adjusted internal forecast is 1.3% which rate is markedly below the required rate of return for a business venture such as Cellplus.”

The very least I can say is that this statement startled me. Where was this fantasy world where investment in mobile telephony operations could reaped quick massive benefits?

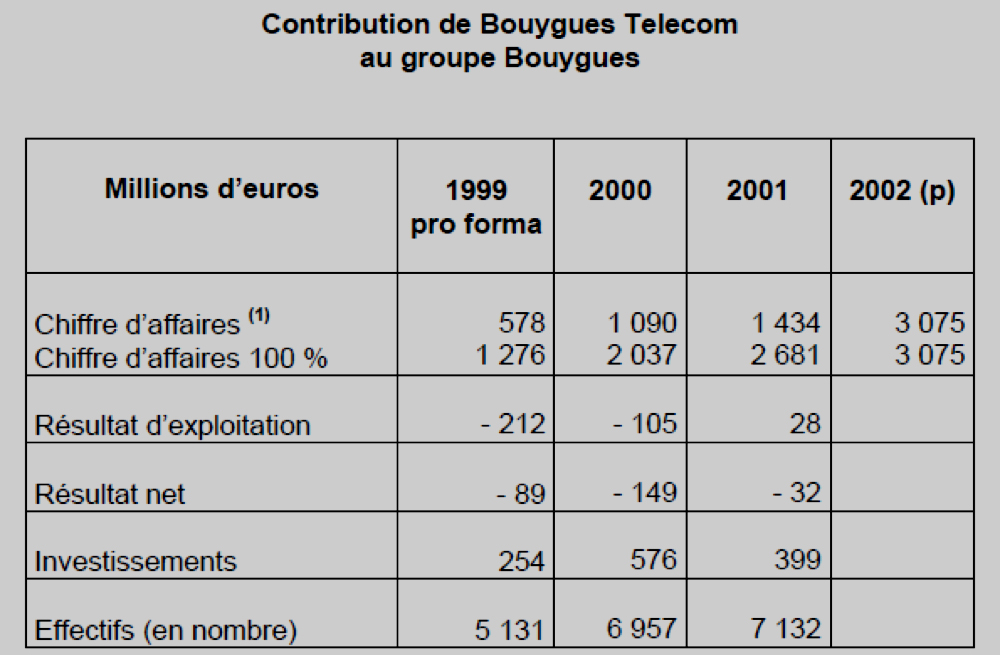

Below an extract of the annual report of Bouygues Telecom (where I used to work):

Bouygues Telecom (a fully privately owned company) obtained its licence in 1994 and started operations in 1996. As at 2001, it was still loss making. However it was a healthy and dynamic company at that time with the shareholders happy to put in more equity and recruit additional staff as illustrated above.

Assuredly, nobody entered the mobile telephony industry for a quick gain. Payback periods, due to the massive capital expenditures, ranged from anything between 8 to 15 years depending on a lot of factors. A parallel could be also drawn with the massive investments happening nowadays in the renewable energy sector through private investors, which are happy with payback periods of 12+ years. (also debunking Paragraph 275 here)

It is easy, with hindsight, to claim that the rate of return designed in the business plans of defendant 2 & 3 was low. In my view, one should not forget that at that time investment in mobile telephony was viewed as high risk especially in low-income countries. Further, no one could predict in the early 90s the massive success and subscriber growth. So defendants 2 & 3 had every right to be prudential in its business plans and the focus in court should have been on achieved rate of returns instead.

In paragraph 272, the plaintiff’s expert witness refers to the possibility of financing of defendant 2 investments through commercial banks. This is surprising as he seems to ignore that loan duration for commercial financing of industrial assets range typically from 5 to 7 years in the country (due to liquidity risk management & local industry practice). I am also guessing that defendant 2 would have required a major portion of the loan to be in foreign currency in order to purchase international goods thus further compounding liquidity risk management issues for the bank providing the funds. In the light of this and considering the loan amount (at that time) and duration (10 years) requirements, there is only a thin probability than defendant 2 could have actually found a bank willing to finance its Investment.

Another avenue would have been through project financing. The plaintiff’s expert witness would be pleased to learn that no local bank was equipped to provide project finance services at that time. In my view therefore, the plaintiff’s expert witness made a misrepresentation of the realities of the telecom industry and while his competence, experience and skills are unquestionable, the question must be asked of his credibility.

Paragraph 167 reads “Mr Forrest takes the view that “an efficient operator’s approved or regulated retail tariff should be broadly in line with its economic costs, or FAC.” FAC stands for fully allocated costs and is the technique which takes into account all the costs … It is also the technique used by Mr Forrest to assess whether Emtel’s domestic tariffs were reasonable when Cellplus entered the market…”

FAC (also known as FDC – fully distributed costs) is a controverted technique used in cost accounting. Below some extracts to sustain this:

1. « Fully distributed cost (FDC) methods enjoy some support because of the false sense of security that comes from (misleadingly) placing costs in one bucket or another. In other words, we may not have all the costs in the right buckets, but at least we know where they are. »

http://warrington.ufl.edu/centers/purc/purcdocs/papers/9121_Berg_Incremental_Costs_for.pdf

Paper by S.Berg , Professor & D.Weisman, Research Fellow, University of Florida

Note : The whole paper is actually very relevant to the case at hands.

2. « The fully-distributed cost (FDC) method is a top-down costing approach that was the dominant form of cost measurement over the past several decades … there are many drawbacks of using FDC, including:

I. The arbitrary nature of determining what constitutes direct costs and common costs

II. The inability to use historical cost data to capture reduced common costs resulting from new technologies, which can result in higher interconnection costs

III. The inability to appropriately allocate costs when changes in traffic patterns occur, causing some services to receive less allocated costs for providing the same service levels.

While the general trend is for countries to move away from FDC, many countries including some members of the European Union continue to rely on FDC. While there is no published comprehensive survey on costing methods used by countries, the alternative use of incremental costing is seen as an effective means of promoting competition in the face of rapidly changing technology. »

http://regulationbodyofknowledge.org/ (Developed by the Public Utility Research Center (PURC) at the University of Florida, in collaboration with the University of Toulouse, the Pontificia Universidad Catolica, the World Bank and a panel of international experts, the Body of Knowledge on Infrastructure Regulation (BoKIR) summarizes some of the best thinking on infrastructure policy)

3. « Le Conseil de la concurrence a, dans un autre secteur, confirmé cette analyse, approuvée par la Cour de cassation, en décidant que dans l'hypothèse où une personne publique en position dominante exerce en monopole une mission de service public et poursuit des activités concurrentielles sur un marché ouvert à la concurrence en utilisant les mêmes ressources pour ces deux activités, il convient de ne prendre en compte que les coûts incrémentaux liés à cette seconde activité, en excluant les coûts fixes communs aux deux activités. »

http://www.autoritedelaconcurrence.fr

Interestingly, the plaintiff’s expert witness advocates the use of incremental costing in paragraph 156 and then resorts to a controverted methodology (FAC) to put forward his claim of cross-subsidisation. How and why the defendants did not challenge this is again beyond understanding. In addition, there is enough literature available to demonstrate that cost accounting (comptabilité analytique in French documents) is a difficult and complex matter which requires time to implement. This was acknowledged in France by “Le Conseil de la Concurrence” and in a judgement delivered in 1997, they wrote:

« CONSEIL DE LA CONCURRENCE - Avis n° 97-A-07

L'Autorité de régulation des télécommunications remarque, dans son avis du 14 mai 1997, que la société nationale France Télécom s'est efforcée de mettre en place une séparation comptable permettant d'individualiser les comptes de la division FTM, conformément aux dispositions réglementaires auxquelles elle est soumise, et estime que les travaux engagés, en liaison avec le cabinet d'audit désigné par le ministre chargé des télécommunications, " devraient contribuer au perfectionnement de la séparation comptable engagée par France Télécom en vue : - d'intégrer au compte de résultats les charges et produits financiers liés au financement et au besoin en fonds de roulement, les provisions pour congés payés et les charges liées aux pensions de retraite ; - d'améliorer l'évaluation des prestations assurées par France Télécom pour le compte des activités de radiotéléphonie, en ce qui concerne l'utilisation du réseau commercial, le potentiel de recherche du CNET et la prise en charge des frais financiers . »

Reading the above, one may justified to ask whether judgement 2017 SCJ 294 is being “plus royaliste que le roi”. Indeed in the above situation, in 1997 an operator in a developed country with far more skilled resources albeit with far more complex operations, is being afforded recognition of its efforts and time to implement the required changes. Whereas in Mauritius, defendants 2 & 3 in a similar situation are being penalized for a period ranging from 1996 to1998 during which their main focus was the launch and success of mobile telephony commercial operations.

The question of whether injection of equity or quasi-equity (capital should be considered as another term for equity without contradiction), emanating from free cash flows of defendant 2 should be considered as cross-subsidisation is a matter of further investigation. It would take too long to dive into this but a quick read of available European jurisprudence indicates that this is a subject of debate.

Paragraph 176, the plaintiff’s expert witness provide a comparison of tariffs between the plaintiff and

operators in countries of “comparable income level”. They also claim that the data which they used

for comparison emanate from the International Telecommunications Union (ITU).

As per IMF guidelines, telecommunication services classify as non-tradable goods. IMF states the following:

“ … Nontraded goods and services tend to be cheaper in low-income than in high-income countries

… Any analysis that fails to take into account these differences in the prices of nontraded goods across countries will underestimate the purchasing power of consumers in emerging market … For this reason, PPP is generally regarded as a better measure …”

As per ITU guidelines, the basis for price comparison should be on GNI (Gross National Income) per capita at PPP (Purchasing Power Parity). I used its close cousin GDP per capita at PPP for comparison below as GNI data was missing for a lot of countries on World Bank database.

Very simply, the three closest countries to Mauritius in terms of GDP per capita at PPP in 1996 are Estonia, Panama Bostwana and should therefore have been used for price comparison. Out of these three countries however, Botswana did not even have any mobile telephony operations at that time!!!

So it would be interesting to analyse the basis on which the plaintiff selected international operators and the methodology they use to compare prices.

Conclusion

The purpose of this article was not to challenge the judgement but rather to shed a light on the matter at hands and to try and provide a different context. In my view, the plaintiff’s claims were debatable and I have tried to demonstrate this. Further the basis on which the plaintiff calculated their claim damages is highly challengeable. The defendants should have challenged 1.) the FAC calculations 2.) the market growth estimates and 3.) the , the put forward by the plaintiff the and I will state again that the level of defense provided by the defendants was weak at the very least.

Publicité

Publicité

Les plus récents